Every shirt you see is sweat-stained. A group of masked faces huddle together by a street crossing. The hum of construction is constant, but not enough to pry eyes away from phones. Polished skyscrapers glisten in the sun, looming over bowed heads. The light turns green, and the mob disperses. Like a sea of synchronised swimmers, moving in strict fashion and with careful intention. Every group member seems like they understand their role, their performance, their duty.

This is an average afternoon in Singapore. A city that never seems to stop. One that craves its routines, whilst making it clear that those routines should not be disrupted. And for the LGBTQ+ community here, that’s exactly how they feel they are regarded: as disruptors of the routine.

In a country predominantly built on the building blocks of conservative values, the livelihood of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals has been a persistent focus of socio-political contention in Singapore for decades.

However, as societal attitudes shift, changes are being made. In August of this year it was announced section 377A of the penal code will be repealed – a colonial-era law that criminalised sex between men. After years of tireless hard work and heavy perseverance, this was the a real step forward for Singapore’s LGBTQ+ communities.

But despite this monumental announcement, the repeal came with its conditions – in particular the continuing censorship of LGBTQ+ media. A day after the announcement, Singapore’s Ministry of Communications and Information (MCI) reaffirmed the Government will continue to uphold LGBTQ+ content restrictions, in order to be “sensitive to societal norms and values.”

So what does the future now look like for LGBTQ+ communities in a post-377A world? After decades of self-led activism, minimal government support and a deeply rooted traditionalist agendas, how are activist groups still fighting for change when their voices are constantly being censored?

“They may not want to believe that these relationships are happening, but the fact is that we exist. And they shouldn’t try and say that we don’t have a voice because of it,” says Ben Xue.

Back in 2006, queer advocacy in Singapore looked a lot different, according to Ben Xue. It was a time when being gay was still a widely taboo topic of discussion, and LGBTQ+ support was virtually non-existent.

“The support landscape back then was very different, a lot more young queer people didn’t find the bars and clubs as a safe enough zone for them to talk about relevant issues.”

19 years old and openly gay at the time, Xue knew that there was a gap in the system that needed to be filled. And so, with the help of two other friends, Xue co-founded the first non-profit queer volunteer group called YoungOutHere (YOH).

“We support young people who lack the sources for support; who are questioning and don’t have supportive parents, a supportive home or school environment, literally bottom of the barrel,” says Xue.

But in response to the announcement of 377A being repealed, Xue, alongside many other queer advocates felt a mix of emotions, particularly in regards to the future of Singapore’s queer media representation.

“The current censorship and guidelines – as they are right now – is not enabling conversations. Instead it’s enabling divide”

Ben Xue

Although young people are able to find their way around Singapore’s media regulations, Xue says the rest of Singapore’s media outreach has stayed relatively conservative, leading to polarising perceptions.

“It’s creating a huge divide, and it’s only getting wider because the media censorship laws are staying the same…it’s making our job a lot harder than it needs to be,” he says.

Kristen Han is an independent journalist and queer activist in Singapore, and has a long, personal history in dealing with the censorship landscape, including a few brushes with the law.

Han says the current media landscape is constructed in a way that allows the government to harness influence and control over the newsrooms.

“The mainstream media is now very influenced and the main newspapers now are directly funded by the government,” says Han.

“We don’t have a lot of independent, credible independent media left, and those that exists are constantly struggling for sustainability – so it’s very difficult.”

Kristen Han

But in a city-state that is also deeply connected to the internet, does Singapore’s main-stream media still uphold the same influence and power it once did?

According to the statistics, it does.

Han believes mainstream media outlets are too close to the government.

“The journalists have become so attuned to toeing the line as an editorial policy, that they’re not really trying. And although individual journalists might be very eager to do more, within the institutional structure they’re very limited.”

Kristen Han

So what exactly does this mean for LGBTQ+ representation in Singapore? According to Han, the censorship of mainstream content is allowing the government to play an active role in shaping society and perspectives on queer topics.

“When you censor all this content, and you make it impossible for people to see positive portrayals of same sex families, then you cannot turn around and say, ‘Oh, look, people are very uncomfortable,'” says Han.

“You’re blocking their access to information, and to seeing people and relating to people, so it becomes very self fulfilling, and it’s not helpful.”

Since the inception of YOH, Xue, alongside the other volunteers have been bridging he gap between young queer kids and their parents, fostering healthy relationships and understandings. Xue believes queer censorship has been damaging for families.

“What young queer kids are viewing versus what their parents are viewing is very different,” he says.

“The system is structured in a way that parents are not being exposed to a lot of the stuff that their kids have been watching. They don’t know what to do, what language to use or how to model their behaviour,

“The censorship is forcing us to deal with this divide. In a very real literal, everyday sense.”

Ben Xue

Advocates say this cycle is continuing, particularly in schools.

20 year old Elijah Tay is a non-binary activist, and for the four years has been a hands-on queer advocate, including creating a shared online forum called My Queer Story SG, which allows LGBTQ+ Singaporeans to share their experiences of queer life with others, whilst maintaining their anonymity.

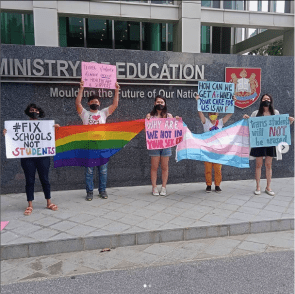

On the 26th of January last year Tay and two others were arrested outside the Ministry of Education, after protesting for the rights of transgender students.

The action was in response to a viral social media post made by a transgender student, who stated that the Ministry of Education had allegedly prevented her from receiving hormonal therapy, as well as the school barring her from attending classes unless she cut her hair and wore the uniform for male students.

“The story drew a lot of attention to just how little the government cares about trans students. And I mean, it’s a conversation that’s been around for years, but its just not talked about in the media,” Tay says.

According to Xue, trans kids in schools are still facing a myriad of challenges with minimal support services in place.

“Trans kids can’t dress in the uniform that they want to feel comfortable in, and at that point you’re basically chasing kids out of school. That’s the bottom line.”

As a non-binary student themselves, Tay says they have experienced multiple instances of gender policing and discrimination in school.

“I feel very uncomfortable being forced to wear a skirt whenever I’m in school… as well, my gender expression to be constantly scrutinised,” says Tay.

“And because the media laws are still in place, the school rules are still fucked up, and we’re continuing to be discriminated against.”

Elijah Tay

June Chua is a transwoman living in Singapore. In 2014, with her late sister Alicia Chua, they founded Singapore’s first and only social service for the transgender community – The T Project.

The program was established in response to what they saw as a growing gap in the existing social service sector, which they felt did not address the needs of the transgender community, especially in terms of homelessness.

“I started sex work when I was 17, and it’s here when I started to notice the underlying issues facing trans people and the risk of being homeless,” Chua says.

“I saw that once a trans person wanted to leave sex work, many didn’t have a family to fall back on, no trans-specific government help, they’re forced to start anew.”

When Chua was 41 she left sex work and, with the help of her sister, decided to try opening a shelter that would serve as a temporary safe haven for homeless trans individuals. By 2016, with the help of the community and allies, The T Project managed to raise approximately $130,000.

“I never realised it would grow so big, beyond my imagination,” she says.

Although the T Project continues work to provide at-risk transgender/gender-non-binary individuals with shelter and support, employment and healthcare needs, Chua says the trans community in Singapore is still being discriminated against, and the lack of media representation has not helped.

“If the media talks to me, I never play into the victimhood. I just talk about the pragmatic and practical things we do at The T project, because I know if I were to talk about rights or equality, that’s when it becomes a sensitive issue for the media, and thats when they would stop reporting,” Chua says.

Chua says this can often lead young trans people feeling confused and unsure of themselves.

“I will always remember this one woman coming in to the shelter. She had just left prison and was immediately sent to an all-male psychiatric hospital. After three months she was finally transferred to us, and she walked in, carrying a Bible in one hand and the Quran in the other – unsure what religion to abide to in order to be accepted. After I told her that we are an agnostic shelter, she looked at me and asked “does that mean I keep my hair long?”

June Chua

In March of this year, The T project was one of the first LGBTQ+ communities to obtain government funding.

Xue says it was a monumental moment for Singapore’s trans community, and hopes the government can continue this support for other queer-led support groups.

“To be registered is the only way the government see you as legitimate. But it’s not just government that sees you legitimate, but also the public sector.”

Xue says the majority of LGBTQ+ communities are denied registry by the government. This means that majority of support groups are completely self-funded.

“We’re fighting against very strong, very well funded emissaries, that are often being platformed because of their conservative agenda. So a lot of responsibility still falls on the community groups to carry that load.”

Even with these growing conversations around lack of queer-specific support in schools, trans homelessness and government registration, advocates say the reality is that these narratives are still not reaching main stream media.

“We still cannot talk about HIV candidly, in the newspapers, or on TV. We have tried to,”

Benedict Thambiah

Former executive director of Action for Aids (AFA), Thambiah has spent many years of his life as a hands-on activist for human rights issues in Singapore. To this day he continues to advocate for HIV/AIDS equality.

But Thambiah describes himself as a realist, and as the news of repeal of 377A was announced, he was not surprised by its conditions.

“I don’t think its going to make much difference because the stigma and discrimination around HIV and AIDS is very well entrenched. And the stigma and discrimination, even against members of the LGBT community is quite entrenched,” he says.

Thambiah says this stigma is largely due to Singapore’s continuing platforming of conservative media, which has lead to a cultivation of misconceptions.

On 29 June 2020, an episode of My Guardian Angels on Singapores free to air Channel 8 was broadcasted, depicting a character as gay, STD-positive and a paedophile.

In response, AFA put out a media statement, which stated “Propagating distorted stories over the most popular free-to-air channels is unbecoming and highly irresponsible and further deepens discrimination and stigma against LGBT people.”

“It was all the worst possible things you can think of, and they put it all in this one person. There were no disclaimers, there’s no education, it was just ‘this is what they are’,”Thambiah says.

The episode continued to receive backlash from the LGBTQ+ communities, and in response, Mediacorp apologised via Instagram, explaining that they had “no intention to disrespect or discriminate against any persons or community.”

“Although they didn’t specify that they would put a stop to these negative portrayals in the future, It was essentially the first time that in my own memory, a TV station has apologised for anything,” Thambiah says.

So what does the future look like for LGBTQ+ media representation in Singapore? One thing seems certain: the voices of activists are getting louder, and their hope for a freer, less censored media landscape in Singapore is one they intend to keep fighting for.

As the traffic light turns red once again and the masked faces and humid bodies gather at the street crossing, the next steps for many queer Singaporeans may still feel unknown. But one thing they feel sure of is that the light will eventually turn green. That the mob will scatter and the skyscrapers will continue to glisten in the afternoon light, and the routines of the LGBTQ+ community will simply be seen as a natural part of the routines of Singapore, their home.

The 2022 Curtin Journalism Singapore Study Tour was funded under the federal government’s New Colombo Plan scheme.